- Acute occlusive arterial disease

- Aneurysm of an upper limb artery

- Thoracic outlet compression syndrome (TOCS)

- Chronic occlusive arterial diseases

Acute occlusive arterial disease

Arteries carry blood, rich in nutrients and oxygen, from the heart to the rest of the body. If the blood flow through the artery to a limb is suddenly reduced – depending on the severity of the flow reduction – the classical symptoms and signs of ischaemia may appear, like severe pain, paleness, coldness, sensation disturbance (numbness, sensation loss) and paralysis (loss of motion).

The commonest cause of sudden blockage (or occlusion) of an upper limb artery is embolization through the bloodstream of a clot formed in the heart. In most cases this is the result of atrial fibrillation or of a heart attack. Other sources of emboli may be lesions in the lining of more proximal large arteries, such as atherosclerotic plaques, aneurysms or traumatic disruptions.

The management of acute limb ischaemia may include: (1) administration of suitable medication to “thin” the blood (“anticoagulation”), (2) embolectomy via a Fogarty catheter (i.e. an operation to remove the embolic material), and (3) correction of the offending condition, if this is feasible.

Aneurysm of an upper limb artery

Aneurysm is a buldging in a weak area of the wall of an artery. In the upper limb, the arteries which most commonly develop an aneurysm are the subclavian, the axillary, the brachial and the ulnar artery in the palm of the hand.

Potential causes can be: atherosclerosis, thoracic outlet compression syndrome, congenital abnormality of the origin and the course of the right subclavian artery, repetitive trauma to the palm etc. All these aneurysms are rare, but may cause serious problems.

Diagnostic approach may include duplex ultrasonography, CT angiography or digital subtractive angiography.

The management of these aneurysms involves appropriate operative or endovascular procedures.

Thoracic outlet compression syndrome (TOCS)

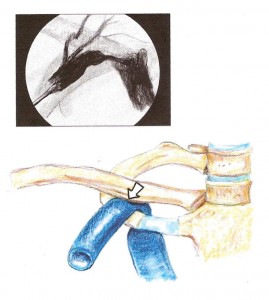

In their course between the base of each side of the neck and the armpit, the nerves (i.e. the brachial plexus) and the vessels (i.e. the subclavian-axillary artery & vein) pass through relatively narrow anatomic compartments bounded by the first rib, the clavicle and certain cervical (the scalene) muscles.

In their course between the base of each side of the neck and the armpit, the nerves (i.e. the brachial plexus) and the vessels (i.e. the subclavian-axillary artery & vein) pass through relatively narrow anatomic compartments bounded by the first rib, the clavicle and certain cervical (the scalene) muscles.

If a part of the brachial plexus, the artery or the vein is compressed (or entrapped) in this narrow space because of an existing anatomic abnormality, then thoracic outlet compression syndrome (TOCS) may arise.

The processes that narrow the space may be classified as structural, functional or post-traumatic. These include

- bony abnormalities such as an extra (i.e. a cervical) rib, an abnormal first rib or an abnormal clavicle

- congenital muscle anomalies, fibrous bands or variant ligaments

- hypertrophic (anterior or medius) scalene muscles due to overuse or non-physiologic use of the shoulder girdle

- fractures

- soft tissue injuries etc.

In view of the anatomical structure mostly affected, the TOCS may be Neurogenic (which accounts for 95% of cases), Arterial or Venous. Accordingly, symptoms include pain, numbness, weakness, coldness, swelling of the limb and skin colour changes.

Considering the Neurogenic TOCS, the ditribution of the pain varies depending on whether the upper or the lower part of the brachial plexus is compressed.

– If the upper part (C5,6,7) is compressed, then pain is referred to the lateral aspect of the neck, shoulder, upper chest, the outside of the arm down to the thumb and index finger.

– If the lower part (C8,T1) is compressed, then pain is referred to the back of the neck, the shoulder-blade, the armpit and the inside of the arm down to the ring and little fingers.

The diagnosis of TOCS may not be straightforward. A variety of clinical provocation tests may be helpful, but occasionally they prove negative though TOCS exists. Investigations which may be requested by the vascular surgeon include duplex ultrasonography and angiography (both are excellent for the evaluation of blood flow in the arteries and veins in the thoracic outlet), computerized tomography (CT) scanning (excellent for evaluation of the bony structures) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning (excellent for demonstrating soft tissue detail including the muscles, nerves, blood vessels and fatty areas of the thoracic outlet). It is also important to carefully investigate for another possible cause of the symptoms, such as a herniated cervical disc, shoulder arthropathy, compression of the ulnar or the median nerve (carpal tunnel syndrome) etc.

The treatment depends upon the clinical form of TOCS. Initially, treatment can be conservative with suitable physiotherapy and neck and shoulder exercises aiming at rebalancing the muscles of the shoulger girdle. When conservative therapy fails, as occurs in the most serious cases of Neurogenic TOCS with unbearable constant pain or reduced function of the limb, and after a thoughtful and frank discussion between doctor and patient, appropriate surgical treatment should be undertaken aiming at widenening the narrow space where the neurovascular bundle is compressed. In the case of Arterial or Venous TOCS with ischaemic or thromboembolic phenomena, thrombolysis or/and appropriate surgical treatment may be required.

EXTERNAL LINKS

- THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/thoracic-outlet-syndrome/basics/definition/CON-20040509

- THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME: An Old Challenge with a New Image http://www.tosmri.com/docs/TOS-White-Paper.pdf

Chronic occlusive arterial diseases

The chronic conditions which can cause reduction of the blood flow in an upper limb comprise a non homogeneous group. Potential causes of chronic ischaemia (i.e. reduction of blood flow) in an upper limb are:

The most common site for atherosclerotic lesions is the initial part of the subclavian artery. The stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian artery is usually symptom free. It may present with reduction in the strength of the pulses and the systolic blood pressure on the affected limb or with a various degree of limb ischaemia. Symptoms of subclavian artery steal (such as dizziness and fainting as the result of sudden reduction of blood flow to the posterior part of the brain during arm exercise) are also rare, although haemodynamic steal, i.e. reverse blood flow in the vertebral artery of the affected side, can frequently be demonstrated by duplex ultrasonography of the neck arteries.

As in all atherosclerotic conditions, quitting smoking, correction of risk factors (dyslipidaemia, hypertension etc) and taking an antiplatelet drug are recommended. Additionally, an appropriate recostructive operation (open arterial surgical procedure or balloon angioplasty/ stenting) may be required.

If there are ischaemic symptoms, an appropriate recostructive operation (open arterial surgical procedure or balloon angioplasty/ stenting) may be required to improve hand perfusion.

We classify vasculitides according to the size of the vessels involved, i.e. large, medium-sized and small vessels. A vasculitic conditions may involve only one or many blood vessels and therefore organ systems. In general. the symptoms are caused by ischaemia of the tissues supplied by the affected vessel. The vasculitic process ranges from a mild obliterative disorder to necrotising vasculitis.

The common types of vasculitis are:

- Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis obliterans)

- Takayasu arteritis.

This is a vasculitis, which causes inflammation and occlusion of large elastic arteries, like the aorta, its branches and the pulmonary arteries. It usually affects young women, 10-30 years of age, and its cause is unknown.

The symptoms can be divided in two phases:

(a) the ones of the acute (systemic) phase, which are non-specific like fever, tiredness and pain in the muscles and joints. During the acute phase, treatment with immunosupression (corticosteroids, cyclophosphamid) may halt progression of the arterial damage, and

(b) the ones of chronic (obliterative or “pulseless”) phase, which depend on which vessels are affected and may include reduction or loss of pulses, inequality of blood pressure between arms and legs, and hypertension. If ischaemic symptoms appear, a suitable procedure may be required (arterial bypass surgery with a graft or balloon angioplasty which is probably the treatment of choice) to increase the blood flow. - Polyarteritis nodosa.

This is a unique process, characterised by a systemic necrotising vasculitis affecting small and medium-sized arteries, such as the ones supplying the kidneys and the bowels.

It may cause proteinuria, progressive renal failure, hypertension, weight loss, abdominal pains, sometimes with blood in the stools, muscle aches and joint pains. Skin manifestations are nailfold infarcts. Diagnostic arteriographic findings are small aneurysm formation and stenoses. Laboratory findings include anaemia, elevated ESR, a positive test for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) & antibody (HBsAb). The treatment of polyarteritis nodosa is corticosteroids and cyclophosphamid. - Vasculitis associated with a connective tissue disease (scleroderma, lupus etc) and Vasculitis secondary to hypersensitivity (to a drug or to an infective agent). This is a small-vessel vasculitis (affecting arterioles, capillaries, venules).

The symptoms with which patients visit the doctor are pain and gangrene due to skin ischaemia of one or more digits. The cornerstone of diagnosis of vasculitis secondary to a connective tissue disease or to hypersensitivity is the finding of an “acute phase response” (elevated ESR, plasma viscosity and C-reactive protein). Also helpful may be certain laboratory tests like full blood count, urinalysis and immunologic screening (RF, RA-test, ΑΝΑ, anti-DNA, C3, C4, ANCA, cryoblobulin, cryoagglutinins, protein electrophoresis etc). However, diagnosis is often only made by analysis of biopsy material.

Last modified 09/09/2020